Why Runners Struggle to Strength Train and How to Get Better

Most runners have probably heard: “you should be strength training.” It’s hard to ignore the benefits: improve your running economy, run faster, prevent injury…I know I want all of those things. Yet when push comes to shove, it’s the first thing to fall off the schedule. I know I’ve been there.

Before PT school, I had a 6-month love affair with weightlifting while in a personal training job. 60-90 minutes a day, 5 days a week. I was the strongest I’ve ever been and gained like 10 lbs. of muscle. When I returned to running, went to PT school, and started working full-time with runners (now 10 lbs. lighter), I realized that runners don’t need, or want, that kind of lifting. And that’s okay.

Why do runners skip strength work, and how can you make it stick better in your routine?

Why It’s Hard for Runners to Strength Train

Based on my own experience and conversations with athletes, barriers to strength training boils down to a few things:

Most strength training programs are overly complicated: Spanish squat, prisoner squat, goblet squat, hack squat, split squat, front squat, back squat…that’s just squats...and we haven’t even talked reps/sets and progressions yet. Or other exercises with many variations.

Strength training isn’t fun for runners: it can’t compete with being outdoors on a good trail.

It’s not “running hard.” A good tempo run will leave me feeling tired but accomplished. Lifting doesn’t give me that same feeling.

It interferes with running - muscle soreness or fatigue can tank your next run.

None of these barriers need to be deal breakers.

The Research Says: Don’t Get Complicated

A 2022 study found that runners who followed a 12-week, running-specific strength training protocol while also running improved both strength and running economy more than runners who just did running-specific workouts. A closer look at the training protocol followed in the study shows a lot of simplicity in the exercise choice:

Weeks 1-6: squats, hamstring curls, calf raises

Weeks 6-12: squats, plyometrics (bounds or hops), hills/sprints

There was weekly progression in this protocol, but the point is that participants only did 3 exercises. That’s it. Not only that, but the strength training protocol incorporated running and supersets of exercises designed to keep the heart rate up. The takeaway is that strength training doesn’t have to be 60 boring minutes of 10 different exercises to make progress as a runner.

My suggestion?

Pick one movement from each of these three buckets and stick with them for 4-6 weeks:

Compound lift (squat, deadlift, step-up, lunge)

Hip/knee support (hamstring curls, hip thrusts, knee extensions, farmer carry marches, plank variation)

Calf/push-off power (calf raises, sled pushes, hops, strideouts)

Every week, add a small progression like a bit more weight or extra set. Every month, pick a new set of movements to work on.

Your goal? Force production and speed, not excessive muscle fatigue

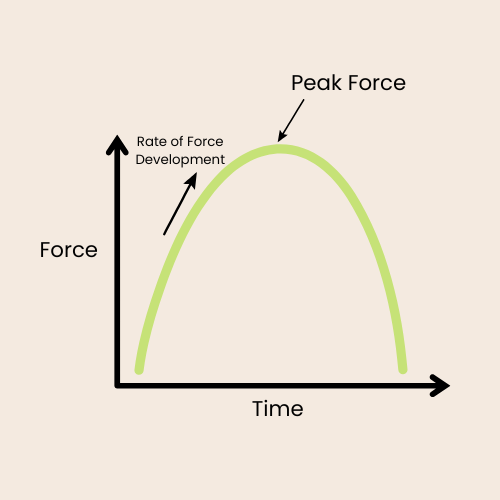

Cadence and stride length do increase as we go faster, but a study done in 2000 in the Journal of Applied Physiology found that runners achieve greater stride length and faster speeds by pushing off harder and faster from the ground. This is driven by:

How much force your muscles can produce (strength).

How quickly your muscles can produce force (power).

Runners who are capable of quickly producing more muscular force likely have a performance advantage over those who cannot.

Imagine a 7:00 min/mile runner who hits 90% of his peak force in his calf every time he hits the ground. Compare that to a similarly trained 7:00 min/mile runner who hits 50% of his peak force. Who fatigues their calf first in a half marathon?

Conventional strength training wisdom says that to improve these attributes, you should be training with a high weight, low rep scheme - and you should be hitting muscle failure on each set. While that might be the optimal approach for someone trying to set a personal best on a back squat, it’s not optimal for runners. Pushing to failure will create more of that muscle soreness, affect your runs, and likely lead to you skipping your next weight session.

Solutions?

If you’re new to strength training, even a lighter weight that is a new challenge to you will create a stimulus to get stronger. 2 sets of 12 is better than none and likely won’t create much soreness.

Once you have some exposure to strength training, absolutely move towards heavier weights. Instead of 5 sets of 5 reps and failing on the 5th rep every time (25 reps), consider 4 sets of 4 where you maybe could have done 6 or 7 (16 reps). This can help reduce post-lifting soreness and leave you feeling fresher for your next run.

To work on explosiveness and be more running-specific, consider trading box jumps or jump rope for 100-meter hill stride-outs or 30 second intervals at mile pace.

Timing Matters

For runners to actually gain the health and performance benefits of strength training, it needs to be a consistent part of your training life. For running economy, it likely takes at least 8-12 weeks according to a 2016 meta-analysis in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. That being said, you can be strategic about how much time you spend on it throughout the year. In my yearly cycle, I tend to run harder in the summer and fall, back off in winter, and pick back up in the springtime. Here’s how strength training looks for me:

Late Spring to Fall - 1x a week, typically less during peaking efforts leading up to a race - these are shorter sessions focusing primarily on maintenance and managing any sore spots that pop up with harder training

Winter - 2x a week - initially focusing on strength first, then explosiveness.

Early Spring - 1-2x a week, focusing on peak strength prior to beginning more intense running blocks.

This annual cycle helps me keep running at the heart of what I do. None of my strength training typically tops 30 minutes at any point during the year.

At the end of the day, the type of strength training you need depends on your goals. If you run to stay healthy, a simple, low-load maintenance program might be all you need. But if you’re chasing a performance edge, strength and power work deserve a spot in your routine.

Either way, it doesn’t need to be overwhelming or all-consuming. A little thoughtful strength work goes a long way toward helping you run faster, feel stronger, and reduce injuries.

REFERENCES

Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements. Peter G. Weyand, Deborah B. Sternlight, Matthew J. Bellizzi, and Seth Wright. Journal of Applied Physiology200089:5,1991-1999.

Effects of Running-Specific Strength Training, Endurance Training, and Concurrent Training on Recreational Endurance Athletes' Performance and Selected Anthropometric Parameters. Prieto-González P, Sedlacek J. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Aug 29;19(17):10773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710773. PMID: 36078489; PMCID: PMC9518107.

Effects of Strength Training on Running Economy in Highly Trained Runners: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Balsalobre-Fernández, Carlos1; Santos-Concejero, Jordan2; Grivas, Gerasimos V.3. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 30(8):p 2361-2368, August 2016. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001316